LA’s scheme to cover a reservoir under 96 million “shade balls” may not be all it is touted to be, experts told FoxNews.com, with some critics going so far as to refer to the plan as a “potential disaster.”

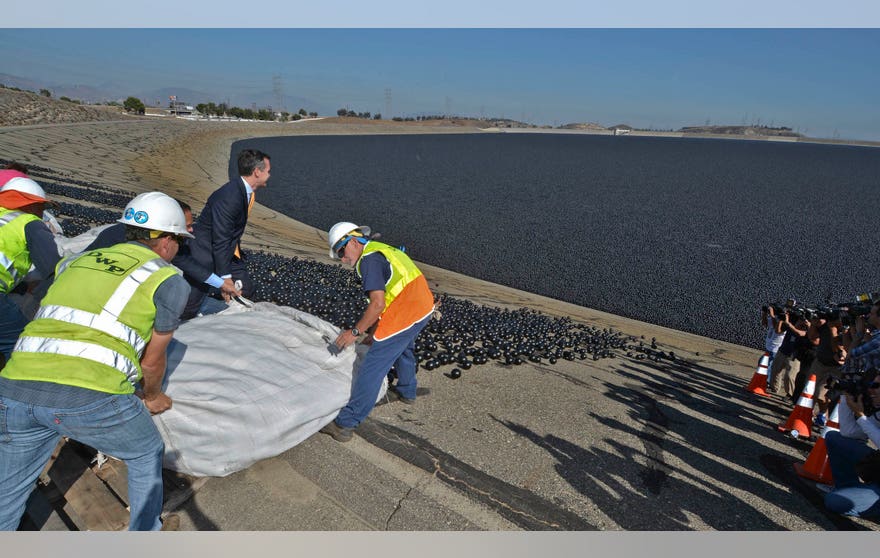

The city made national headlines last week when Mayor Eric Garcetti and Department of Water officials dumped $34.5 million worth of the tiny, black plastic balls into the city’s 175-acre Van Norman Complex reservoir in the Sylmar section. Garcetti said the balls would create a surface layer that would block 300 million gallons from evaporating amid the state’s crippling drought and save taxpayers $250 million.

Experts differed over the best color for the tiny plastic balls, with one telling FoxNews.com they should have been white and another saying a chrome color would be optimal. But all agreed that the worst color for the job is the one LA chose.

“Black spheres resting in the hot sun will form a thermal blanket speeding evaporation as well as providing a huge amount of new surface area for the hot water to breed bacteria,” said Matt MacLeod, founder of the California biotech firm Modest Moon Farms. “Disaster. It’s going to be a bacterial nightmare.”

“It’s going to be a bacterial nightmare.”

– Matt MacLeod, Modern Moon Farms

Any color covering will help stop wind-driven evaporation, said Robert Shibatani. principal hydrologist for the Sacramento-based environmental consultant The Shibitani Group. But when it comes to the hot summer sun sucking water out of the reservoir, color is everything, he said.

“Ideally you would want a chrome surface,” he said. “The worst would be matte black, which has a reflectivity close to zero.”

Biologist Nathan Krekula, a professor of health science at Bryant & Stratton College in Milwaukee, said black balls will absorb heat, transfer it to the water and cause evaporation. And he agreed with MacLeod that the heat will prove hospitable to bacteria.

Los Angeles City Councilman Mitch Englander, Mayor Eric Garcetti (wearing a yellow tie) and LADWP workers deposit the final installment of 96 million shade balls into the Los Angeles Reservoir. (Art Mochizuki, LADWP)

“Bacteria required a few things to grow a dark, warm and moist environment,” he said. “The balls will give them the perfect environment to live in.

“What works in backyard fish pond does not always transfer to large scale system such as this, Krekula added. “Keeping the balls clean when covered in bacteria and mold slime will be a monumental task.”

Dennis Santiago, a risk analyst for Torrance-based Total Bank Solutions, suspects the real goal for the black-ball cover is to avoid steep Environmental Protection Agency fines. The federal agency’s “Long-Term 2 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule,” announced in 2006, would require public and private water utilities to spend billions to cover open-air reservoirs that hold treated water to prevent contamination. Officials in several districts around the nation have balked at the EPA mandate, notably in New York, where lawmakers are fighting to block a $1.6 billion concrete cover the EPA has ordered built over a Yonkers reservoir.

“This is not about evaporation,” Santiago said. “The water savings spin is purely political. What the black balls are really about is that [Los Angeles] needs to stay in-compliance with an EPA requirement to place a physical cover over potable water reservoirs.”

Garcetti’s office did note that the ball covering provides a “cost-effective investment that brings the LA Reservoir into compliance with new federal water quality mandates,” but its emphasis on blocking evaporation was the clear focus at the event. Los Angeles Department of Water spokesman Albert Rodriguez told FoxNews.com the city has plenty of time to get in compliance with the EPA.

While this latest shade ball initiative continues to generate publicity, it is not the first time Los Angeles utilized the concept. After high levels of bromate, a potentially carcinogenic chemical, were found in the Silver Lake and Ivanhoe reservoirs in 2008, the Department of Water deployed the balls.

Sydney Chase, president of XavierC, one of the shade ball supply companies behind the project, said the color is a result of pure black carbon being added to the high density polyethylene plastic to take in ultra-violet rays and subsequently stop sunlight from penetrating the plastic. Any other color would have required dyes, said Rodriguez, which could have then leached into the water while the carbon black does not.

Editor’s Note: The name of Matt MacLeod’s firm was incorrectly identified in a previous version of this story. The error has been corrected.