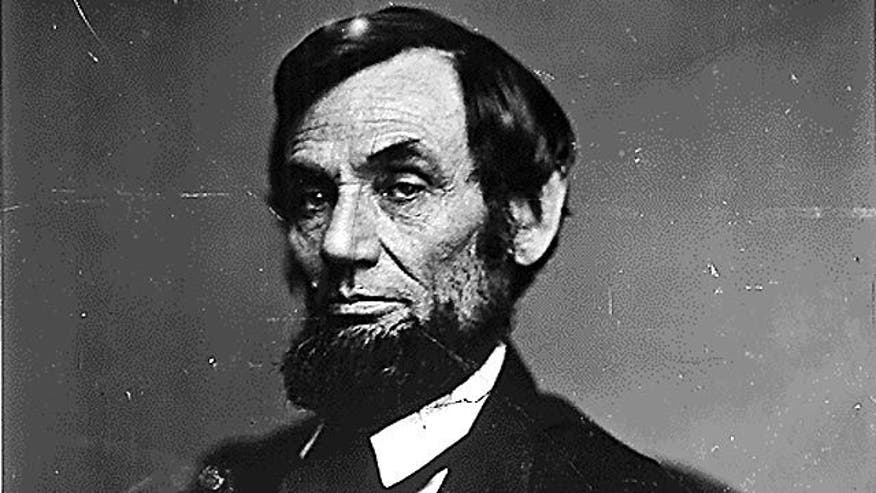

More than any other president, Abraham Lincoln shapes our idealized conception of the presidency. That is, the commander-in-chief as an austere figure, burdened by the office, yet sternly resolved to finish the mission. Humble in origin, somber in humility, yet still capable of lifting the country with the power of his oratory, now and forever. A man tragic in his own lifetime, and immortal in ours.

Lincoln had little in the way of formal education. Still, he knew his Bible and his Shakespeare, and so the stately cadences and poetic but measured flights found in those books molded his own speech. And ever since, creative minds have sought new ways to breathe new life into his words. In “Lincoln,” the just-opened movie from Steven Spielberg, the Sixteenth President’s most famous speech, the Gettysburg Address, is delivered in a unique way–by white and black soldiers of the Union Army, reciting the lines back to their author.

Yes, Lincoln, the gifted orator, inspired others. Walt Whitman, arguably America’s greatest poet, was moved to write one of his most famous works, “O Captain! My Captain!” in the weeks after Lincoln’s assassination in 1865:

O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done;

The ship has weather’d every rack, the prize we sought is won;

The port is near, the bells I hear, the people all exulting,

While follow eyes the stead keel, the vessel grim and daring.

But O heart! heart! heart!

O the bleeding drops of red!

Where on the deck my captain lies,

Fallen cold and dead.

That’s Lincoln as most Americans know him: hero, martyr, and an obvious choice for enshrinement on Mt. Rushmore and so many other hallowed places across the nation that he had saved.

It’s no wonder, then, that for the last century-and-a-half, every one of the 28 presidents since has had to compare and contrast himself, in some way, to Lincoln. Earlier this month on ABC News, President Obama showed anchor Diane Sawyer the portrait of Lincoln he keeps in the Oval Office; when asked by Sawyer what he thinks about when he gazes upon that painting, Obama answered, “This job’s not supposed to be easy.” Indeed.

Spielberg’s new movie shows how Lincoln’s presidency came to set the bar so high. Those looking for a sprawling Civil War epic will be disappointed; we see glimpses of combat, but no glorious cavalry charges and no stirring battle speeches. Instead, the focus is more on the sorrow and the pity–the aftermath of fighting.

In one poignant scene, the president makes his way through the battlefield at Petersburg, Virginia, site of a recent Union victory, still strewn with the fallen, both Blue and Grey; the solemn leader tips his stovepipe hat to the dead of both sides.

As Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote in her 2005 book, “Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln” — which provided much of the source material for the movie — Lincoln had “the rare wisdom of a temperament that consistently displayed an uncommon magnanimity to those who opposed him.”

The film focuses on the last four months of Lincoln’s life, January to April, 1865. And yet in that brief period, we see three key aspects of him–as a war leader, as a politician, as a family man.

First, as a war leader, Lincoln wanted the killing to stop; yet even more, he wanted not only to win a victory but also to free the slaves. So he was willing to consider negotiations with the South, but only as a prelude to surrender and the ending of slavery. Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens could not bring himself to go that far, and so the bloodshed ended only with Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, portrayed in a quietly ennobling scene between Lee and Ulysses S. Grant; decades before, the two men had been classmates at West Point.

Lincoln the war leader is the Lincoln we know best. He was the commander-in-chief who promised “a new birth of freedom” in 1863, on the consecrated ground of Gettysburg. Yet he was also the man who huddled over telegraph machines at the War Department, straining to learn the latest news, good or bad, from the battlefront. And while he kept his eyes on the strategic prize, he also amused his soldiers with salty jokes and stories. That’s Lincoln, as portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis, in a character-inhabiting performance sure to garner an Academy Award nomination.

Second, as a politician, Lincoln had to win passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery forever. The amendment had passed through the US Senate in 1864; next it had make its way through the US House, also by a two-thirds majority. Here we are reminded that politics necessarily has its pragmatic, even grubby, side–and some might even say that Lincoln’s operatives engaged in outright bribery. Meanwhile, the not-always-so-loyal opposition in the House, led by New York Democrat Fernando Wood–played scene-stealingly by a young Peter Lawford look-and-soundalike, Lee Pace–fought Lincoln and the Republicans at every turn.

Meanwhile, Lincoln had to restrain the amendment’s most ardent supporters, including Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, leader of the so-called “Radical Republican” faction. Stevens–played by Tommy Lee Jones in another Oscar-worthy role–threatened to upset the delicate calculus of enactment by pushing too hard and for too much; he wanted not only emancipation of the slaves, but also the confiscation of Southern plantation properties. In the end, Lincoln and his allies were able to push hard enough, but not too hard; the amendment passed the House by a vote of 119-56 on January 31, 1865. Having abolished that ancient and horrible institution, the US could finally enter fully into the modern era.

Third, as a family man, Lincoln felt the burden of a loving but difficult wife, Mary, played by Sally Field–in a third performance calling for an Oscar nomination. Abe loved Molly, as he called her, but she made his home life, one might say, challenging. On the other hand, Mary had lost two of her four children to disease at a young age, and she was sick at the thought of her eldest surviving son, Robert, joining the military–not an untypical concern for any mother.

And that was part of Lincoln’s appeal: He was no aristocrat, he was one of one us. As the poet Whitman, who never met Lincoln–although he saw him from afar in Washington, DC as Lincoln would go to visit wounded soldiers whom Whitman had volunteered to nurse–was moved to observe, years after Lincoln’s death, “After my dear, dear mother, I guess Lincoln gets almost nearer to me than anybody else.”

By the end of the war, Robert Lincoln was able to overcome his mother’s wishes and join the staff of Gen. Grant, who is himself portrayed in the film by Jared Harris as a steely and purposeful leader.

Spielberg’s “Lincoln” is definitely a history lesson, and so sometimes it drifts into talkiness. But of course, it’s important history–and every American should know it.

Toward the end of the film, as the Thirteenth Amendment is passed, the Republicans break into a rendition of a famous song of that era, “The Battle Cry of Freedom”:

The Union forever! Hurrah, boys, hurrah!

Down with the traitor, up with the star;

While we rally round the flag, boys, rally once again,

Shouting the battle cry of freedom!

Few could fault the Unionists for letting their passions run high. After all, the Civil War left more than 620,000 Americans dead; the equivalent death toll among the US population today would be more than six million.

Yet as the film makes clear, Lincoln himself set the better benchmark of vision and generosity. As he said in his second inaugural address, on March 4, 1865, as the war still raged:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

A high standard, to be sure. And perhaps only the Great Emancipator himself could live up to that standard. As the film reminds us, upon Lincoln’s death, at 7:22 am on April 15, 1865, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, tears streaming down his warrior face, declared, “Now he belongs to the ages.” To be sure, Lincoln still inspires.

As Whitman wrote in the final stanza of his poem:

My captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still;

My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will.

The ship is anchor’d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done:

From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won!

Exult, O shores! and ring, O bells!

But I, with silent tread,

Walk the spot my captain lies

Fallen cold and dead.

That’s the Lincoln who will always haunt our memory, urging us, by the quiet power of his stoic example, to heed, in our own time, the better angels of our nature.

James P. Pinkerton is a Fox News contributor. He is a former White House domestic policy adviser to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush.